Ten years after massacre of 32 reporters, Philippine justice on trial

On the eve of the 10th anniversary of the biggest massacre of journalists in history – on 23 November 2009 in Maguindanao province, in the southern Philippines – Reporters Without Borders (RSF) urges the judges in charge of the case to finally end the impunity that continues to characterize this shocking crime.

The families of the victims have been waiting for ten years. The justice system has been unable to convict those responsible for ten years. And the murders of a total of 58 people, including 32 journalists, have gone unpunished for ten years.

The reporters were accompanying a group of supporters of a local politician, Esmael Mangudadatu, who were travelling in convoy to file his papers to run for the post of Maguindanao governor against Andal Ampatuan Jr, then governor Andal Ampatuan Sr’s son. They were ambushed and slaughtered in the town of Ampatuan by around 100 men who used a mechanical shovel to bury the bodies in a common grave.

It is hoped that a regional court in Quezon, 1,400 km north of Maguindanao, will issue verdicts in the case by 20 December at the latest, finally ending the impunity that has accompanied this massacre and ending the long wait that the victims’ families have had to endure.

“I feel that not every one of them will be convicted, but I hope at least the principal suspects will get convicted,” Grace Morales, the widow of one of the victims, News Focus TV reporter Rosell Morales, told RSF. “The evidence is there. It palpable that they did this gruesome crime, but it's taking them years to figure it out. It has been too long already.”

“All eyes are turned towards Judge Jocelyn Solis-Reyes and the Quezon court, who have the historic duty to convict those responsible for the massacre in Ampatuan,” said Daniel Bastard, the head of RSF’s Asia-Pacific desk.

“The impunity surrounding the massacre of all these journalists is all the more unbearable because it has resonated throughout the country as an encouragement to eliminate reporters who annoy all-powerful local despots. The credibility of the rule of law in the Philippines is at stake, along with respect for the families of the murdered journalists.”

The names of the presumed perpetrators have long been known. They are members of the Ampatuan clan, the all-powerful political dynasty in Maguindanao province, whose favourite son, Andal Ampatuan Jr, planned to succeed his father as governor and did not welcome Esmael Mangudadatu’s decision to run against him.

“A contact told us about the Ampatuans' threat to chop up Mangudadatu,” Nonoy Espina, told RSF. Espina was covering the region at the time for the Dateline Philippines website and, like many other journalists, he had planned to cover the filing of Mangudadatu’s candidacy papers. But, at the last moment, a flu attack kept him in bed. His colleagues were not so lucky.

“Still nursing a fever, I got a text on 23 November saying the convoy was missing. I thought they were just held up at a checkpoint or something, until a couple of hours later, another text said: ‘Convoy located. All dead’.”

Judicial machinery obstructed

Now chair of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) and ten years ago its director, Espina was one of the first reporters to reach the scene of the massacre. “I felt my knees literally turn to jelly,” he said. But his priority was to report the tragedy objectively and contact the families of the victims. At least 195 suspects were quickly identified.

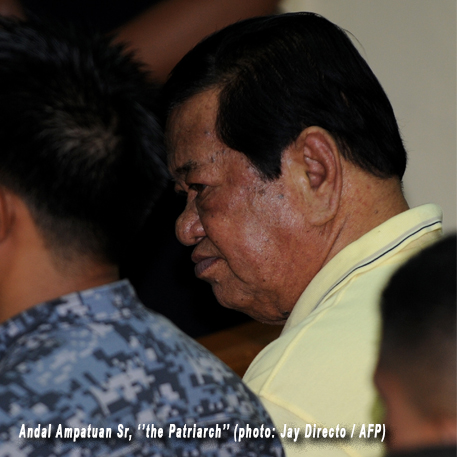

From the start, the judicial machinery was obstructed by members of the Ampatuan family including “El Padre,” Andal Ampatuan Sr, its patriarch and mastermind, and governor at the time of the massacre. Because of his status as the clan’s godfather, he was quickly charged as the massacre’s presumed instigator.

Philippines Daily Inquirer correspondent Aquiles Zonio revealed in 2010 that he had received death threats designed to dissuade him from testifying against the patriarch and his men. He also reported cases of intimidation, threats and violence against police officers who had written reports implicating the Ampatuan family. Andal Ampatuan Sr finally died of liver cancer in 2015 without having been brought to trial.

The No. 2 suspect, Andal Ampatuan Jr, is regarded as the massacre’s ring-leader. Several witnesses say he actually led the group of 100 men who staged the ambush and carried out the massacre. He was reportedly accompanied by his brothers Zaldy and Sajid Islam, and his cousin Akmad, who acted as his lieutenants.

From the judicial viewpoint, it should have been an open-and-shut case. But that is to ignore the judicial system’s rampant corruption. It was reported in 2014 that certain prosecutors were deliberately delaying investigations in return for bribes. Progress in the proceedings slowed right down.

Pressures

Witnesses and other persons involved in the case have been the targets of bribery attempts, threats and in one case – one of the Ampatuan family’s drivers in 2014 – even murder. Andal Ampatuan Jr’s allies have repeatedly put pressure on a key witness, deputy mayor Sukarno Badal, who ended up standing by his testimony that he saw Andal Ampatuan Jr shoot people during the massacre.

Andal Ampatuan Jr was finally arrested and, despite repeated requests for their release on bail, he and his brother Zaldy will remain in detention until the verdict. But, like 80 other suspects, Sajid Islam Ampatuan is free. He was released in 2015 on bail of 11.6 million pesos (200,000 euros) and has since been elected major of a town in Maguindanao province twice.

“That it has to take a decade for a verdict to be handed down for such a heinous crime is already a great injustice,” said Espina, who nonetheless does not blame the judges for the delays.

“More than the judicial system, it is an indictment of our system of governance, where the national leadership allows clans like the Ampatuans to amass so much wealth and power while turning a blind eye to their excesses because they need these families' support. The result is a culture of impunity that emboldens even more atrocities.”

According to RSF’s tally, a total of 14 journalists have been murdered in the Philippines since Rodrigo Duterte became president in June 2016, most of them because they had criticized local potentates. No one has so far been convicted for any of these murders.

The Philippines is ranked 134th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2018 World Press Freedom Index.