JOURNALISTS HELD HOSTAGE

1-The figures

54

Journalists currently held hostage

+4% compared to 2016

Comprising

44 professional journalists

7 citizen-journalists

3 media workers

Hostages: RSF regards journalists as hostages when they are being held by non-state actors that threaten to kill or injure them, or continue to hold them as means of pressure on a third party (a government, organization, or group) with the aim of forcing the third party to take a particular action. Hostages may be taken for political reasons, economic reasons, (for ransom) or both.

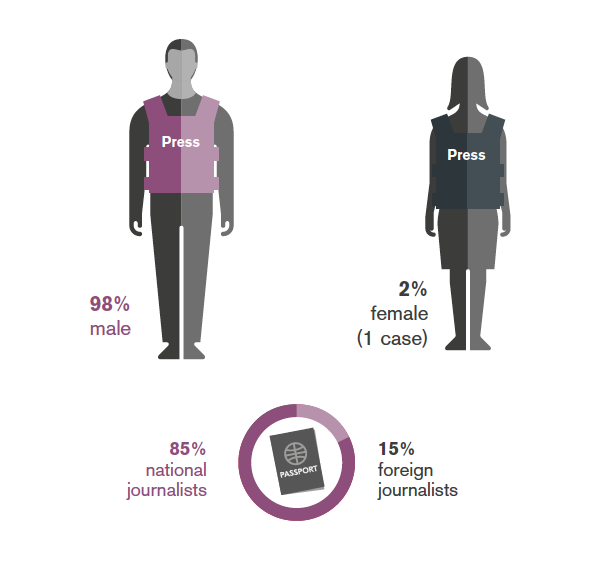

Worldwide, a total of 54 journalists are currently held hostage, compared with 52 on the same date a year ago (a 4% increase). While the number of foreign hostages has increased slightly (+14%), more than three quarters of the hostages are national journalists -- often poorly paid freelancers working in extremely risky conditions. Citizen-journalists are now paying a heavy price. A total ofseven citizen-journalists are currently held by armed groups, compared with four this time last year. The increase confirms their growing involvement in the gathering of news and information, especially in war zones that have become inaccessible to professional journalists.

Concentrated in four countries

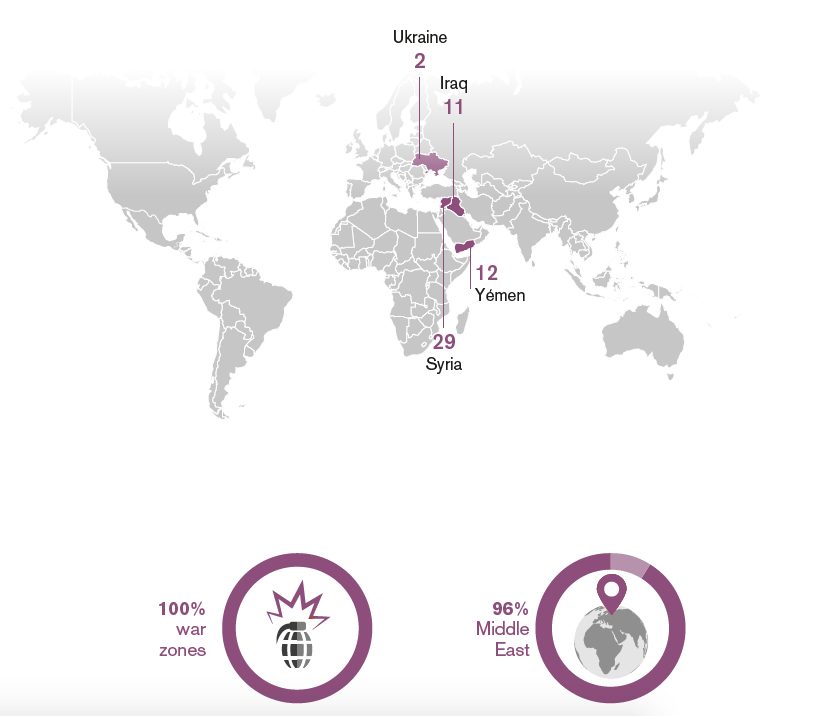

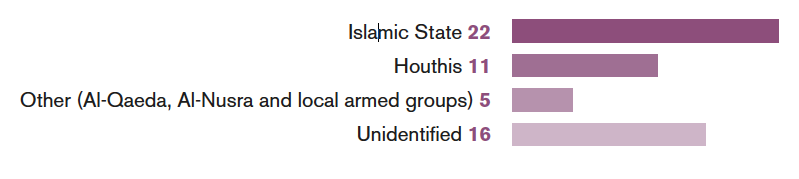

The Middle East’s fracture lines continue to be the world’s most dangerous regions for journalists. Yemen is sinking ever deeper into a war in which one of the factions, the Houthis, tolerate no criticism and are now holding 11 journalists and media workers, compared with 16 this time last year. Another journalist is being held hostage in Yemen by Al-Qaeda. Meanwhile, in Syria and Iraq, 40 journalists continue to be held by Islamic State and other radical Islamist groups such as Al-Nusra.

Outside the Middle East, the only country with hostages is Ukraine, where the separatist forces in the east tend to regard the few remaining critical journalists as spies. Two journalists are currently held in the self-proclaimed “republics” of the Donbass This is far fewer than at the peak near the start of the conflict in 2014, a year when more than 30 journalists were kidnapped. The decline in the intensity of the fighting, the fact that the front line is now stationary, and the almost complete absence of critical or foreign reporters in the separatist areas have all helped to reduce the practice of hostage-taking.

The main hostage-takers

For armed groups, abduction is a business that is profitable and practical in many ways. It allows them to impose terror and obtain the complete submission of potential observers while using ransoms to fund their war. The increase seen this year in the number of hostages in Syria and Iraq is nonetheless due mainly to the fact that RSF has included cases that had not previously been tallied, either because they were still being verified or because the families did not want their cases made public.

While the overall number of hostages has not changed significantly, the military setbacks suffered by Islamic State in 2017 and the loss of its main strongholds on both sides of the border between Iraq and Syria have not yet been reflected in any improvement in the safety of journalists. A South African photo-journalist, Shiraaz Mohamed, was kidnapped at the start of the year (see below in Syria, No.1 for foreign hostages).

RSF has not been able to obtain any information about the journalists who were held hostage in the cities of Mosul and Raqqa, which were recently retaken by Iraqi forces and a US-backed Arab-Kurdish coalition. The creation of “de-escalation zones” in the spring of 2017 with the aim of ending violence in several Syrian regions has not been accompanied

by any visible improvement for hostages. The relatives of the activist and citizen-journalist Samar Saleh and her fiancé Mohamed al-Omar, who was freelancing for the Syrian opposition broadcaster Orient TV, are still without news of them. They were kidnapped on a street in Atareb, a town near Aleppo, on August 9, 2013 while filming its reconstruction. Atareb is now located in one of the de-escalation zones where the opposing forces are supposed to observe a cease-fire.

2-Media blackout

At least 22 Syrian journalists and 11 Iraqi journalists are currently held hostage in their respective countries. The exact number of national journalists in captivity is still hard to calculate, as the families and colleagues often prefer not to report their disappearance for fear of disrupting negotiations and delaying their release. It is often the kidnappers themselves who insist on silence. The media blackout may last for several years in some cases. More than three years went by before Kamaran Najm’s capture was revealed.

A respected Iraqi photo-journalist, Najm was injured and kidnapped by Islamic State on June 12, 2014 while covering fighting between Kurdish Peshmerga and IS in the Kirkuk region. Najm not only worked for such prestigious international media outlets as Der Spiegel, The Times, Vanity Fair, Washington Post and NPR but also founded the first Iraqi photo agency Metrography. The day after his abduction, his kidnappers allowed him to call a relative to confirm that he had been abducted and to warn that he could be endangered by any media attention to his abduction. His family and colleagues said nothing for three years. They finally lifted the media blackout because his abductors never contacted them again.

3-Syria, No.1 for foreign hostages

As far as RSF knows, seven foreign journalists are currently held hostage in Syria. Three of them have been held for more than five years. Austin Tice, an American journalist who worked for the Washington Post and Al Jazeera English, and Bashar al-Kadumi, a Jordanian journalist who worked for Al-Hurra TV, were abducted in August 2012. Tice was abducted in a Damascus suburb; al-Kadumi in Aleppo. According to RSF’s information, Tice is not being held by an Islamist group.

The British reporter John Cantlie was abducted a few months later, in November 2012, along with his American colleague James Foley, who was murdered by Islamic State on August 19, 2014. Cantile has not been treated as a typical hostage by his captors. Used by his abductors for media propaganda, he has been shown from time to time in staged videos praising Islamic State, each time appearing more haggard and emaciated. His last appearance, on the streets of Mosul, was in December 2016.

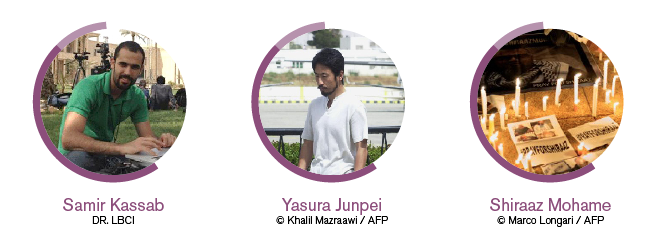

As with national journalists, the fate of kidnapped foreign journalists is largely unknown. Even the exact identity of their kidnappers is often hard to establish. A Sky News Arabia crew consisting of Mauritanian reporter Ishak Moctar and Lebanese cameraman Samir Kassab, disappeared while reporting in Aleppo in October 2013. The Lebanese newspaper Al Joumhouria reported six months later that they were alive and had been moved to Raqqa province but provided no further detail. There has been no news of them since then.

Japanese freelance journalist Jumpei Yasuda has been a hostage since the summer of 2015. Since then, the only proof that he is still alive has been a video recorded on his 42nd birthday in March 2016. It contained no indication of his kidnappers’ identity. Nothing is known about the current status of Shiraaz Mohamed, a South African freelance photo-journalist who was working for the Gift of the Givers Foundation when he was abducted along with two of the foundation’s employees near the Turkish border in January. They were kidnapped by individuals who identified themselves as “representatives of all the armed groups in Syria” and said they wanted to “settle a misunderstanding.” They released the two employees but not Mohamed. His family and the NGO continue to await evidence that he is still alive.

>>Read more: