International regulations: broken or blocked by lobbies

The Human Rights Council’s resolutions are not binding and are not an effective way to restrain those states that are the worst violators of individual online freedoms.

Another Human Rights Council resolution, adopted in September 2016, noted that, “in the digital age, encryption and anonymity tools have become vital for many journalists to exercise freely their work and their enjoyment of human rights, in particular their rights to freedom of expression and to privacy, including to secure their communications and to protect the confidentiality of their sources,” and called on Member States “not to interfere with the use of such technologies, with any restrictions thereon complying with States’ obligations under international human rights law.”

However, the Human Rights Council’s resolutions are not binding and are not an effective way to restrain those states that are the worst violators of individual online freedoms.

Ever since Edward Snowden’s revelations and the end of US hegemony over Internet governance, the Enemies of the Internet have been trying to increase their role in Internet regulation, above all via such UN agencies as the International Telecommunication Union, UNESCO and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, which have all issued declarations on the defence of fundamental freedoms online and Internet governance. Following the Declaration of Principles issued at the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) in Geneva in 2014, the WSIS has been one of the main multilateral platforms on Internet governance, but it has issued no binding resolutions designed to prevent authoritarian regimes from subjecting their citizens to mass censorship and surveillance.

“There is a growing danger that the struggle over the strategic issue of Internet governance will end up officialising a fragmented and censored Internet,” said Benjamin Ismaïl, the head of RSF’s Asia desk. “If every country demands sovereignty over the Internet, we will have a system that grants authoritarian regimes every right to restrict online free speech and information. To avoid this, it is essential that binding international mechanisms are put in place to guarantee the existence of a global free Internet. Now more than ever, this guarantee requires control of Internet companies and companies that export mass surveillance technology.”

In June 2014, RSF began asking the UN Human Rights Council to establish an international convention on corporate responsibility with regard to human rights, with the aim of making governments place strict controls on the export of surveillance technology and establish effective recourse for individuals who have been the victims of surveillance and the terrible consequences that can result from it (arrest, imprisonment, physical violence and torture).

A few months later, on 28 November 2014, RSF, Privacy International, Digitale Gesellschaft, the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and Human Rights Watch hailed the European Union’s decision to add new forms of surveillance technology to the list of dual-use goods and technologies subject to export controls. It was “Europe’s first step towards increased control of surveillance technology,” RSF said. Members of the Coalition Against Unlawful Surveillance Exports (CAUSE) – Reporters Without Borders, Amnesty International, Digitale Gesellschaft, FIDH, Human Rights Watch, Open Technology Institute and Privacy International – sent a joint open letter on 2 December 2014 to members of the Wassenaar Arrangement, a grouping of 41 nations – most of them EU members – that regulates the export of conventional arms and dual-use goods and technologies. Referring to the Wassenaar Arrangement upcoming plenary session, the letter urged the groupe to take measures to curb the alarming proliferation of surveillance technology available to authoritarian regimes known to systematically violate human rights.

Nearly three years after these calls for effective control of the private sector, the EU appears to be in retreat.

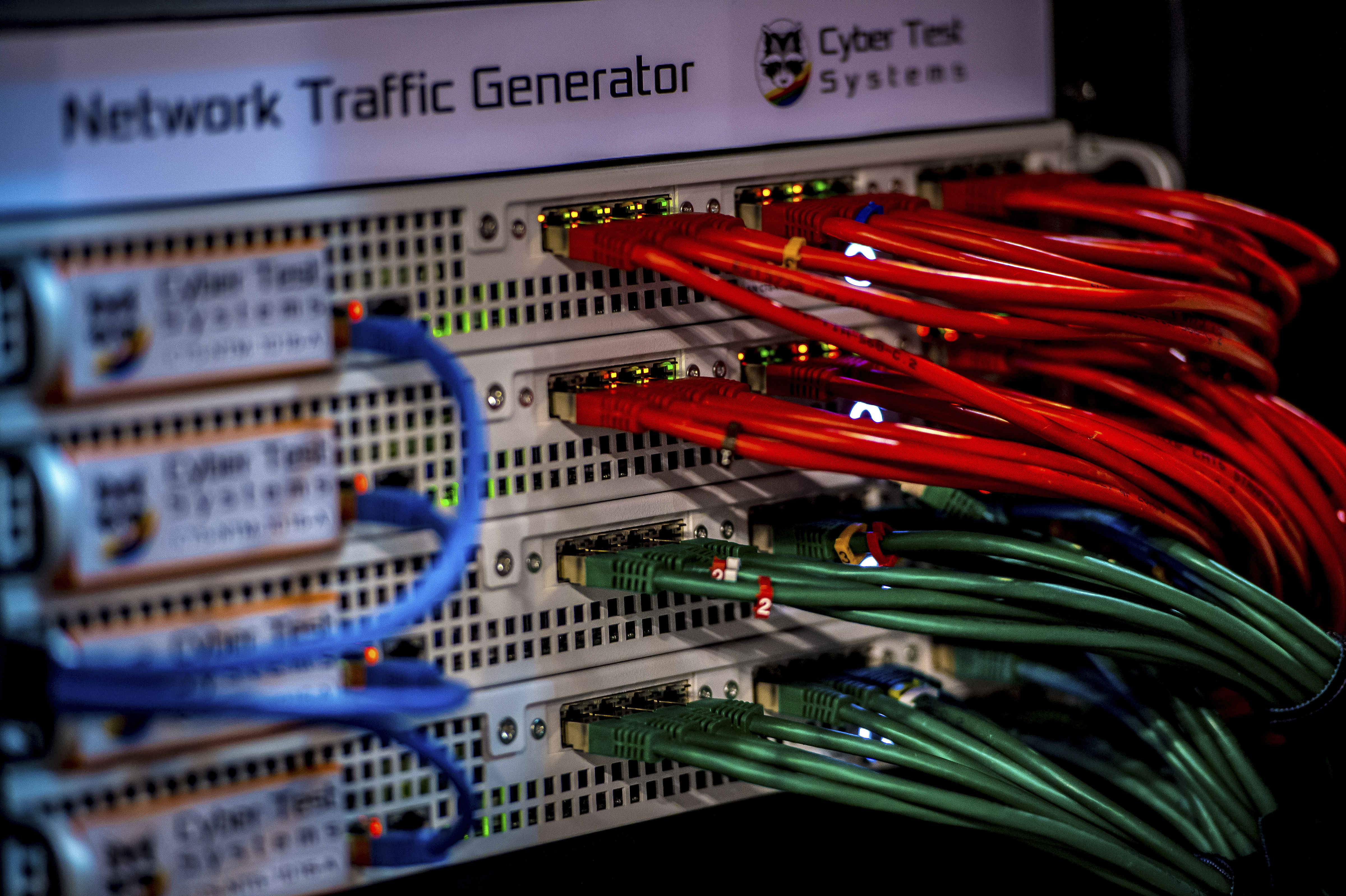

Regulation of surveillance technology exports has ground to a halt as a result of pressure from the digital technology industry lobby. Represented above all by the DigitalEurope association, whose executive board includes representatives of such companies as Nokia, Siemens, AMETIC, IBM, ANITEC, Cisco and Microsoft, and backed by a group of diplomats from nine countries (Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Poland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom), this lobby has managed to get telecommunications interception equipment, intrusion software, surveillance centres and data storage systems removed from the initial list of technology subject to control in the regulation proposed by the European Parliament and Council.

The latest proposal no longer contains the originally envisaged controls on biometric equipment, geolocation systems or deep packet inspection technology (DPI), which enables inspection of data packets as they move through the Internet. By using DPI, governments bent on surveillance can access the content of emails, instant messaging, and VoIP conversations, and can see whether or not an email or message is encrypted. The latest proposal also fails to obligate EU member states to tell the public which companies have been given permission to export.

Within the United Nations, the European Union and most national legislation, regulation of Internet surveillance, data protection and surveillance technology exports is still incomplete and inadequate with regard to international human rights norms and standards. The need for a legislative framework that protects online freedoms continues to be primordial with regard to both the issue of Internet surveillance as a whole and the particular problem of companies that export surveillance technology.

>> IV - RSF’s recommendations on cyber-censorship

II <<