Dire year for journalists under state of emergency in Turkey

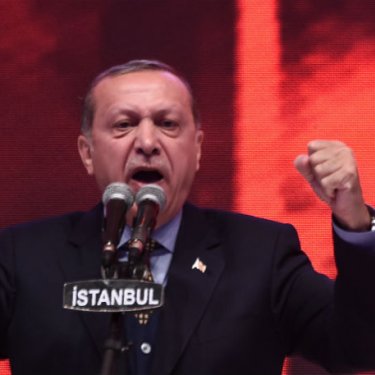

A year after an attempted coup, the level of media freedom in Turkey is abysmal, as the following assessment by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) shows. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government has used a state of emergency to step up a witch-hunt against critics. Turkish journalism is in its death throes.

A year ago, on 15 July 2016, the Turkish people managed to thwart a bloody coup attempt. But instead of reflecting the people’s democratic aspirations in its response, the government has carried out an unprecedented crackdown on the pretext of combatting those responsible for the failed coup.

The state of emergency declared five days after the coup attempt has allowed the government to summarily close dozens of media outlets. And Turkey, which is ranked 155th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2017 World Press Freedom Index, is now the world’s biggest prison for professional journalists, with more than 100 detained.

“We call on the Turkish authorities to immediately release all Turkish journalists who have been imprisoned in connection with their work and to restore the pluralism that has been eliminated by the state of emergency,” said Johann Bihr, the head of RSF’s Eastern Europe and Central Asia desk.

“Prolonged arbitrary detention without reason and the isolation of detainees must be regarded as forms of mistreatment. Until Turkey restores real possibilities of legal recourse, we call on the European Court of Human Rights to issue a ruling as quickly as possible in order to end this tragedy.”

Prison first, trial later

Nearly a year without trial

The arrival of the first anniversary of the coup attempt means that most of the detained journalists are approaching the first anniversary of their arrest. But the indictments only began being issued in the spring and the big trials are only now starting to get under way.

The “justices of the peace,” the regime’s new henchmen, systematically order pre-trial detention and usually reject release requests without taking the trouble to offer legal reasons.

Thirty employees of the daily newspaper Zaman – 20 of whom have been held for nearly a year – will finally begin being tried in Istanbul on 18 September. These journalists, who include Şahin Alpay, Mümtazer Türköne and Mustafa Ünal, are each facing three life sentences.

Their crime is simply having worked for an opposition newspaper that was closed by decree in July 2016. The indictment describes Zaman as the “press mouthpiece” of the movement led by Fethullah Gülen, the US-based Turkish cleric who is accused of masterminding the attempted coup.

This means they are charged with “membership of an illegal organization” and involvement in the coup attempt. Orhan Kemal Cengiz, a lawyer and former columnist, is also facing life imprisonment simply for having acted as Zaman’s defence lawyer.

The release of 21 other journalists was blocked at the last moment on 31 March and the judges who had ordered their release were suspended. The Istanbul prosecutor’s office provided the grounds for this U-turn by initiating new proceedings against 13 of these journalists – including Murat Aksoy and Atilla Taş – for “complicity” in the coup.

They are due to appear in court on 16 August on this additional charge as well as the previously existing one of membership of the Gülen Movement. Each of them is now facing the possibility of two life sentences.

The well known journalists Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan and Nazlı Ilıcak will have spent a year in detention when their trial resumes on 19 September in Istanbul. They are accused of transmitting “subliminal messages” in support of the coup during a broadcast. They and 14 other journalists who are co-defendants are facing the possibility of three life sentences plus an additional 15-year term.

In the provinces, conditional releases have slowly been granted to some journalists accused of complicity with the Gülen Movement. In Antalya, Zaman correspondents Özkan Mayda and Osman Yakut were released on 24 May after eight months in provisional detention.

But in Adana, Aytekin Gezici and Abdullah Özyurt, two journalists who are part of a group of 13 people accused of membership of the Gülen Movement, are still in prison. The trials continue in both cases, with the possibility of long prison sentences.

New spate of arrests

The trial of 17 journalists and other employees of the republican daily newspaper Cumhuriyet will start in Istanbul on 24 July. Eleven of them, including editor Murat Sabuncu, columnist Kadri Gürsel, cartoonist Musa Kart and investigative reporter Ahmet Şık, have been held for the past seven to nine months. Charged with links to various “terrorist” groups because of the newspaper’s editorial policies, they are facing up to 43 years in prison.

But the harassment of this newspaper has not stopped there. On the grounds of a tweet deleted after 55 seconds, Cumhuriyet website editor Oğuz Güven is now facing the possibility of ten and a half years in prison on a charge of Gülen Movement propaganda. He was freed conditionally in mid-June after a month in pre-trial detention.

Sözcü, a national daily that is one of the few remaining government critics, is now also being targeted. Mediha Olgun, the news editor of its website, and Gökmen Ulu, one of its reporters, were jailed on 26 May for publishing an article on the eve of the failed coup about where Erdoğan was on holiday. They are charged with the “attempted murder of the president” and supporting the Gülen Movement.

Universal state of exception

The systematic use of pre-trial detention is not just applied in case of alleged complicity in the coup attempt. Not a week goes by without more arbitrary arrests of journalists. They include Tunca Öğreten and Ömer Çelik, who have been detained since late December in connection with their revelations about Erdoğan’s son-in-law, energy minister Berat Albayrak.

Documentary filmmaker Kazım Kızıl spent nearly three months in provisional detention in Izmir before being released under judicial control on 10 July. Arrested while covering a demonstration, he was accused of “insulting the president” in his tweets.

The authorities have also used the state of emergency to silence the remaining critics on the Kurdish issue. The justice system, which is more politicized than ever, tends to treat anything related to this issue as terrorist in nature.

In the trials of participants in a campaign of solidarity with the pro-Kurdish newspaper Özgür Gündem, a prison sentence was issued for the first time on 16 May against journalist and human rights defender Murat Çelikkan.

Appalling prison conditions

Ailing detainees denied release

Şahin Alpay, a 73-year-old former Zaman columnist, has respiratory and cardiac problems, and is diabetic. He cannot sleep without the aid of a respiratory mask in his cell in the top-security prison in Silivri. But this has not stopped the judicial authorities from extending his provisional detention for the past year.

The situation is the same for 72-year-old Nazlı Ilıcak, a veteran of Turkish journalism and politics. Ayşenur Parıldak, a young Zaman reporter detained since August 2016, has been in very poor psychological health ever since her release, ordered by an Ankara court, was blocked at the last minute in May. Her family fears that she could take her own life.

Isolation – another form of mistreatment

RSF regards the prolonged isolation of Turkish detainees – including the reduction of visits to the barest minimum and a ban on correspondence – as a form of mistreatment. Its victims include Die Welt correspondent Deniz Yücel, a journalist with Turkish and German dual nationality who has been in pre-trial detention since February.

He is charged with “propaganda for a terrorist organization” for interviewing Cemil Bayık, one of the PKK’s leaders. But in reality he is a hostage of the diplomatic dispute between Turkey and Germany, with President Erdoğan referring to him publicly as a “traitor” and a “terrorist.”

His lawyer, Veysel Ok, said: “He is in total isolation, denied contact with anyone aside from the visits from his lawyers and members of his family. With one or two exceptions, he is not allowed to send or receive letters. His indictment has still not been prepared. And we have still not been able to see his case file, because of judicial investigation confidentiality.”

Like other civil society activists, RSF’s Turkey representative, Erol Önderoglu, has sent postcards to many imprisoned journalists. But these postcards have never been delivered.

Trampling on defence rights

Veysel Ok is also defending the well-known novelist and columnist Ahmet Altan. He described to RSF how the state of emergency is violating this client’s right to legal defence.

“I am allowed only one hour a week to discuss the indictment and the dozens of appended files with my client,” Ok said. “An exchange of documents with him takes at least 20 days. The papers have to go through the prison management, the Bakırköy prosecutor’s office, the Çağlayan prosecutor’s office and finally the court that is handling the case. It is impossible to prepare for the trial properly under these circumstances.”

Year-long denial of justice

European Court – last hope for jailed journalists

Turkey’s constitutional court used to play a key role in efforts to ensure respect for free speech, but it has been paralysed since the state of emergency was declared. The cases of many of the imprisoned journalists have been referred to the court but it has yet to issue a ruling on any of them.

In the absence of any effective legal recourse, more and more imprisoned journalists have turned to the European Court of Human Rights, whose decisions are binding on the Turkish state. So far, the appeals of around 20 of these imprisoned journalists have been registered with the court, including Şahin Alpay, Murat Aksoy, Ahmet Altan, Deniz Yücel and Ahmet Şık.

RSF organized a demonstration outside the court’s headquarters in Strasbourg on 29 May to highlight the fact that all hopes are now pinned on the court. A few days later, after 10 months of waiting and negotiating, the court amended its statutes, allowing it more flexibility in the order in which it handles cases. The court can now give priority to cases from Turkey, Russia and Azerbaijan even if they do not involve “the right to life or health.”

No recourse for pluralism

More than 150 media outlets have been closed without reference to the courts. They have been closed by decrees issued under the state of emergency. Media pluralism has been reduced to a handful of low-circulation newspapers.

Around 20 of the closed media outlets were eventually allowed to reopen, but the overwhelming majority have had no right of recourse. The left-wing TV channel Hayatın Sesi, the pro-Kurdish daily Özgür Gündem and many other outlets have appealed to the constitutional court in vain. Given this inaction, the lawyers of the pro-Kurdish TV channel, IMC TV, have also referred its closure to the European Court of Human Rights.

The constitutional court may nonetheless relinquish part of its responsibilities to a new Commission of Appeal that the Turkish authorities created in February 2017 in an attempt to avoid international condemnation.

This commission is supposed to examine the appeals of some 200,000 individuals who have been targets of administrative sanctions, and the appeals of media outlets, associations and foundation that have been liquidated under the state of emergency.

However, the Commission of Appeal is not yet operational. It will begin receiving cases on 23 July. And there are serious doubts about its independence, given that five of its seven members are named by the government.

Arbitrary administrative sanctions

The lack of legal recourse has also affected the many journalists who have been the targets of administrative sanctions in the past year, including the withdrawal of press cards, the cancellation of passports and the seizure of assets.

The targeted journalists include Kutlu Esendemir, who learned at the Istanbul airport on 2 April that his passport had been cancelled as part of an investigation into Karar, a newspaper he worked for. There has so far been no response to the appeal that he filed three days later with the Istanbul prosecutor’s office.

It was almost a year ago that Dilek Dündar was banned from leaving Turkey to join her husband, Can Dündar, a journalist forced to flee to Germany. After waiting for months for an explanation from the justice ministry, she appealed to the constitutional court, but the court has yet to respond.

Read RSF's previous reports on the crackdown in Turkey since the coup attempt:

- “State of emergency, state of arbitrary” (19 September 2016)

- “Journalism in death throes after six months of emergency” (19 January 2017)